As the 2022 Artist in Residence of the Amsterdam Academy of Architecture, I brought together spatial designers and climate justice organisers for a week-long programme. It combined a training on just transition and an assignment to anticipate how

Below is the shortened and revised transcript of the introduction lecture, June 30th, 2022. Full publication available on AvB Winterschool website.Royal DutchShell infrastructure will be decommissioned and repurposed in the coming decades.

Let’s Talk About Shell.

In May 2019, at the Circustheater in Scheveningen, the shareholders of Royal Dutch Shell were having their Annual General Meeting, just as they have been for the last 20 years. Joining them for an intervention was the spokesperson for codeROOD, a grassroots disobedient climate action collective I was part of. When it was her turn at the microphone, she declared that the people present there were witnessing ‘a historic day’: that it would be the last Shell shareholder meeting ever to be held. She went on to explain that in the midst of a climate emergency, the last thing we needed was exactly what was happening here: continuing business-as-usual, maximising shareholder value with short-term profits. We wanted to make sure this would never, ever, happen again. This was the launch of the Shell Must Fall campaign; we thought it would be quite decent to inform the board of directors first.

Little did we know that a year later her prediction would turn out to be true. Sadly enough, it wasn’t our action that cancelled the meeting: we were just 100 days before “one of the most exciting mass actions yet” when the pandemic cancelled any such gathering. Then last year, the company decided to move its headquarters to London, citing vague reasons like ‘streamlining operations’. But even the Financial Times remarked that “there are clear reasons why Shell wants to leave the Netherlands, where climate activism led to a May court judgement ordering Shell to cut more emissions by 2030.” Alongside the tax benefits they would gain in the UK, this ‘capital flight’ was the result of the mounting pressure from climate activists. The campaign is far from over: our fellow organisers in the UK also caused massive disruptions to the company’s first-ever shareholder meeting in London earlier this year.

You may be wondering why I am talking to spatial designers gathered here for the kick off of a winter summer school about the company formerly known as “Royal Dutch” Shell. What I would actually like to talk about is designing a rapid, just, and comprehensive eco-social transition. But unfortunately, we have some concrete obstacles like Shell in front of us. Dislodging these obstacles is a precondition for a just transition. I believe there is merit in focusing on a concrete case study like Shell, instead of talking about an abstract ‘energy transition’. Consider Shell the perfect case study that encapsulates broader issues of Western global extractivism, Dutch colonialism, financial speculation and corporate control.

Of course, the entanglement of overdeveloped societies with carbon pollution is a complex matter. But there is absolutely no doubt about the paramount responsibility and culpability of the energy industry. A handful of companies have dominated the sector and profited from fossil fuels and their derivatives. They have built corporate empires with geopolitical, infrastructural, financial, and ideological underpinnings. These companies have known about the consequences of their actions all my life, and yet, they doubled down on this path. They have manufactured dangerous distractions like greenwashing, ‘carbon footprint’ and ‘carbon offsetting’ to divert attention and deny their role.

I was one of the 17,000 co-plaintiffs alongside Milieudefensie and other organisations who sued Royal Dutch Shell. And last year, we won the case. The court in The Hague agreed that the human rights consequences of climate breakdown are more important than the company’s right to operate freely and profit from extracting and burning fossil fuels. Now the company is being held responsible for the so-called “scope 3” emissions, and it has to halve its total emissions within this decade.

This is unprecedented, but only the beginning. There is no viable business model for Shell. Its current legal and financial form is inadequate for implementing the changes required by the court case and demanded by the people. As long as Shell remains a ‘public limited company’, it cannot keep fossil fuels in the ground. It cannot decommission its infrastructure. It cannot provide a fair deal for its ex-workers, nor compensate damaged communities, nor repair ecosystems. In short, it cannot put itself out of business.

If it cannot be nudged in the right direction to make voluntary, incremental adjustments, then deep structural changes can only be enforced upon Shell: radically and responsibly restructuring its ownership, control and purpose, by any legal, economic and political means necessary. Call it dismantling, decommissioning, sunsetting, phasing out or retiring: this is necessary, overdue and inevitable.

Shell might be moving on from its Dutch past, but let’s remember how it still benefits from social acceptance and national pride in this country. So let’s talk about Shell, here, in this winter summer school. By extension, let’s also talk about our role, complicity and responsibility as designers in this land, and let’s talk about what we can do.

Speaking of the complicity of designers, I would like to introduce you to a very special architect. Will Gains is an Architectural Designer at Bowman Riley. He has designed and built an electric car charging station for Shell. Shell website says that “Will’s hugely excited about the idea of working with Shell to create the EV hub of the future.” Let’s hear from Will himself, who is featured in an advertisement that portrays him as a problem-solving, birdbox-building, overengineering aficionado and keen cyclist:

WILL: (…) I’m currently working on developing a design for an EV charge hub, where electric vehicles can go and charge up their batteries. This is the first time a full Shell petrol station has been transformed into a full EV charge centre. As a keen cyclist, it’s a real positive thing to work on a project that promotes more electric cars on the road. (…)

VOICEOVER: Thanks to the innovation of people like Will, Shell’s first electric-only station in the UK is taking shape. [#MakeTheFuture]

“Thanks to the innovation of people like Will”, Shell is able to greenwash and design-wash its image. Make no mistake: Shell spends more money on marketing than on renewables, on which it spends only a few percentage points of its total investments. Will probably gets his over-engineered birdhouse charging station paid from the marketing budget. Not to mention EV charge stations are an utterly misguided, ineffectual and false solution to decarbonising mobility, let alone tackling lithium extractivism, improving public transport, or reclaiming urban space. To summarise: Will designed a charging station for Shell. That’s greenwashing. Then Will played in advertising for Shell. That’s also greenwashing. My advice for you: Don’t be Will.

Just Transition, System Change and Postcapitalism

The decades of great transformation are ahead of us. There is a big role for designers, especially in repurposing vacant buildings, reclaiming defunct industries and regenerating damaged territories. And yet this is not just a matter of technical expertise; it also requires navigating complex ethical considerations. What kind of energy transition are we going for? Do we wish energy giants like Shell to become green capitalist renewable monopolies, or do we want to turn them into a decommodified, cooperative energy democracy?

There is a slogan by climate justice organiser Quinton Sankofa from the USA: “Transition is inevitable. Justice is not. Let’s get to work.” What do we mean when we say ‘just’ transition? Isn’t everything we do to reduce carbon emissions inherently a good thing? Shouldn’t we just indiscriminately use every tool at our disposal to stop global heating? Yes and no; there might be a right time for some things, and there are other things that will inevitably make things worse. If overdeveloped countries had started with individual action and market-based solutions fifty years ago, they may have delivered a version of green capitalism, perhaps delaying crossing the biophysical limits of the planet by a century. Maybe a point will be reached where tweaking the geochemical composition of the planet will be desperately needed to lessen some of the worst impacts. In a volatile world, solutions need to be emergent and contextual.

Some things are certain: the time for incremental measures within the coordinates of capitalism is over. At this late hour, nothing short of system change is going to work. We have centuries of decolonial and anticapitalist critique, decades of scientific evidence and an incontestable intergenerational duty grounding this. Claiming otherwise has many flavours: market fundamentalism, climate denial, climate delayism, growth fanaticism, eco-modernism, eco-fascism. I’m afraid these are at best desperate coping mechanisms, and at worst anti-humanist and anti-naturalist death drives.

If you want a numerical approximation for what I mean by system change, consider this: radical reductions imply halving emissions every decade until mid-century, and then keeping that balance carbon-negative at least until the end of the century. This means that the biggest, most impactful chunk of decarbonisation has to happen first. There is no such thing as ‘starting modestly and increasing ambitions’, as it is often expressed by technocratic politicians. In this Decade Zero, even the latest IPCC report recognised the need to give up on economic growth. Here is another numerical approximation for system change: carbon pollution per capita is so grossly unequal (with 10% of the world population responsible for half the emissions, and half of the population responsible for 10% of emissions), that abolishing carbon privileges of the few is the fastest, least disruptive and most effective way to get started.

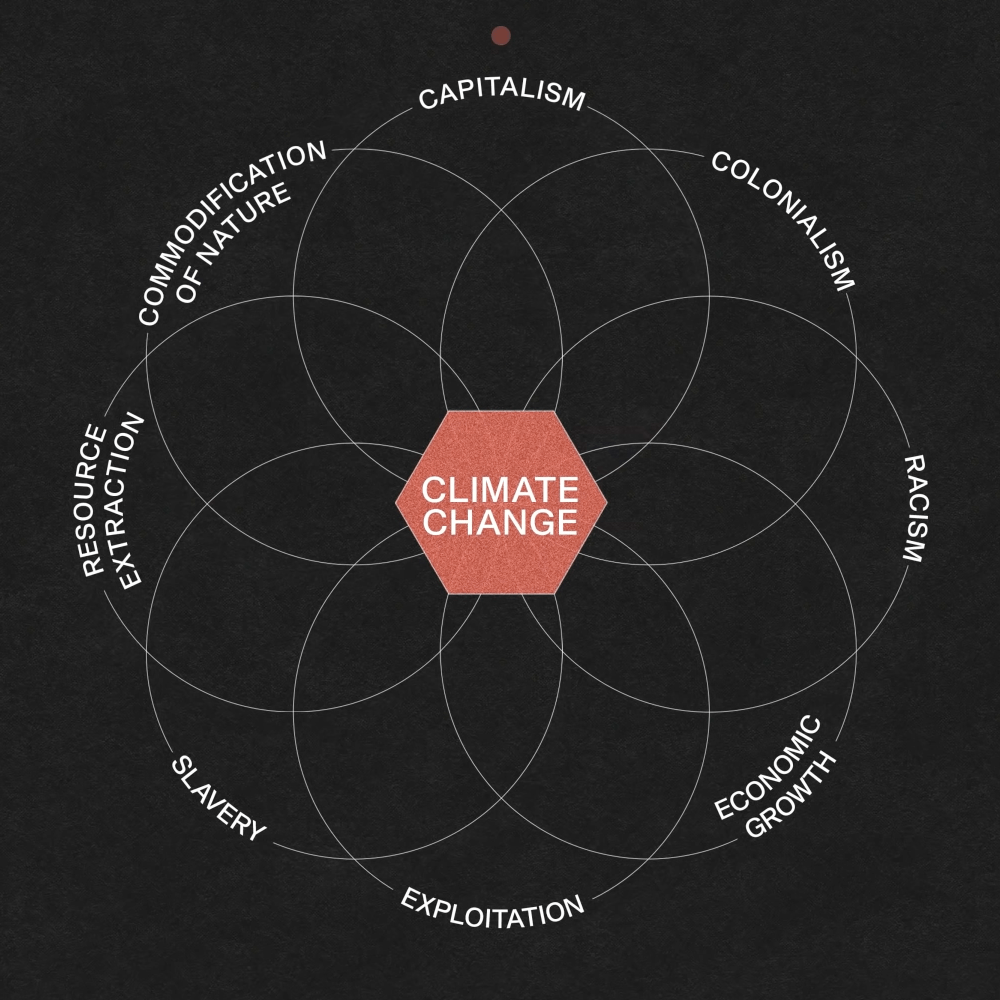

So in that sense, justice is not an add-on to the laundry list of an already complex and exhaustive set of techno-scientifically determined transformations that need to happen. It is a moral compass, a practical field guide, and frankly, the only politically realistic program that doesn’t involve perpetuating and aggravating already entrenched mass suffering. Intersecting issues, struggles and solutions is how you build power, resilience and diversity on this unjust, damaged but not yet entirely broken planet. In other words, there are no quick fixes and no silver-bullet solutions, but the patient, careful, intricate work of weaving environmental, economic, political and racial justice into the tapestry of social progress.

It is impossible to capture the complexity of it all, but I will share two slogans that hint at the ethos of a just transition: “Return, Repair, Regenerate”: defend indigenous sovereignty over occupied territories and against extractivist projects; restore impacted landscapes, watersheds and coastlines; expand biodiverse ecosystems by rewilding. “Decarbonise, Decommodify, Democratise, Decolonise”: transform energy systems towards clean, socialised, publicly-owned models, by dismantling their extractivist, productivist, capitalist and (neo)colonial power structures. Before you claim any ‘green’ credentials for your next design project, ask yourself: how much are you fulfilling these 3Rs and 4Ds?

Prefiguration, Speculation and Design

I would like to give “Shell” another layer of meaning, and in doing so, I would like to introduce some design-political concepts to structure our work. The Industrial Workers of the World is an international, revolutionary, industrial labour union, founded in Chicago in 1905. The Preamble of their Constitution ends with the following statement:

It is the historic mission of the working class to do away with capitalism. The army of production must be organized, not only for everyday struggle with capitalists, but also to carry on production when capitalism shall have been overthrown. By organizing industrially we are forming the structure of the new society within the shell of the old.

It is such a vividly architectural metaphor: to preserve the structural elements of something to build something new. Call it adaptive reuse, but applied to an entire economic and civilisational model. Note that the strategic focus is on organising within industrial production, with the expectation that once capitalism is over, its industrial legacy would be inherited and carried on. Today, this position is simply indefensible. The colonial, capitalist and industrial paradigms are indistinguishable. Extractivism is the closest term that captures the core logic of their continued legacy.

I’d like to complement and contrast this quote with another iconic revolutionary statement. Buenaventura Durruti was a Spanish anarcho-syndicalist Civil War hero. When asked whether victory is worth it if the country will be in ruins, he is attributed with the following answer:

We have always lived in slums and holes in the wall. We will know how to accommodate ourselves for a while. For you must not forget that we can also build. It is we who built these palaces and cities, here in Spain and America and everywhere. We, the workers. We can build others to take their place. And better ones. We are not in the least afraid of ruins. We are going to inherit the earth; there is not the slightest doubt about that. The bourgeoisie might blast and ruin its own world before it leaves the stage of history. We carry a new world here, in our hearts. That world is growing in this minute.

While I admire Durruti’s strong revolutionary utopian attitude, shouldn’t we be afraid of a world in ruins, when it is not just the built environment, but the very fabric of life that is disintegrating in front of our eyes? If I grossly simplify, the Preamble and Durruti represent two opposing revolutionary strategies: ‘we are going to inherit productive infrastructure’ vs. ‘we are going to build out of capitalist ruins’. The revolutionary question might have given way to the question of transition, but it appears that our pathways are no different a century later.

The good news is that the expression ‘from the shell of the old’, means something radically different for later generations. Quite the opposite actually: since the 60s, the expression has been repurposed by the feminist, ecologist and pacifist strands of the New Left, to signify what has become known as prefigurative politics. To pre-figure means to ‘anticipate or enact the preferable future in the present, as though it has already been achieved’. To shape things in the present the way we’d like them to be in the future. So the emphasis is on already forming the new society, growing the new world, by means of carving out spaces that foreshadow and precipitate the new society, hollowing out the spaces of the old world.

Let’s call this new world and new society, for lack of a better word, postcapitalism. Postcapitalism is neither a historical inevitability nor an ever-present alternative; it is rather the narrow emergency pathway to avoid civilisational collapse and mass extinction. Given the circumstances, we don’t even have the luxury to have a fully coherent, positive, utopian project; postcapitalism is rather leaving the riddle of history unsolved, it is what we fill the void of the shell with, it is what flourishes from capitalist ruins. The task of postcapitalist designers is to give shape, meaning and purpose to those actions. In his 2017 book, Postcapitalism: A Guide to Our Future, Paul Mason remarks:

We have to design the transition to postcapitalism. Because most theorists of postcapitalism either just declared it to exist, or predicted it as an inevitability, few considered the problems of transition. So one of the first tasks is to outline and test a range of models showing how such a transitional economy might work.

Neither simply desiring nor observing postcapitalism, ‘designing the transition to postcapitalism’ is done by ‘outlining and testing a range of models’. In other words, combining speculation and prefiguration. If design can be both prefigurative and speculative, then postcapitalism can indeed be designed, the means and the ends of the transition reconciled. I believe near-term, plausible, hopeful speculative fiction can be indistinguishable from strategic policy recommendations. Perhaps storytelling (and visionary fiction) can set the transition in motion. So I encourage you to embrace your most speculative designer selves in this winter summer school. I challenge you to prove Fredric Jameson wrong, and make the end of capitalism easier to imagine than the end of the world.

This winter summer school is a provocation and an invitation to spatial designers: Are we ready for this gigantic challenge? Do we have what it takes to be a designer of the just transition? Are we capable of letting go of eco-modernist, solutionist, techno-fix ideologies? How can we simultaneously prefigure commoning practices and speculate postcapitalist futures? Can we put your skills and privileges into the service of the most impacted communities? How will we design for care, repair and justice? This is history calling us. Are we going to answer?

Leave a comment