This is a position paper I drafted together with LOOM for a “Just Transition Lab” project proposal in October 2022.

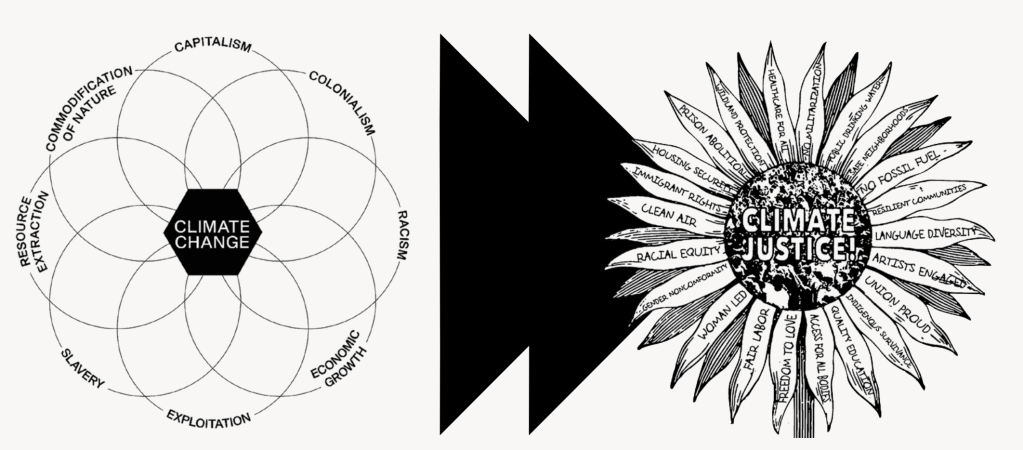

Our understanding of Climate Justice has been developed through more than a decade of climate-focused practice in organising campaigns, curating exhibitions and advising policymakers, but it is ultimately rooted in the key concerns and vocabulary of the global climate movement. Combining environmental, economic, social and racial justice analyses, a foundational precept for Climate Justice can be summarised as the “leadership of the most impacted”. If climate injustice is the result of centuries of colonialism, capitalism and extractivism that entrenched structural asymmetries (oppressor/oppressed, exploiter/exploited and polluter/polluted), Climate Justice calls for intersectional, international and intergenerational solidarity to empower, protect and support the Most Affected People and Areas (MAPA). As a political project, it intends to reverse the power and debt relations between the overdeveloped and the underdeveloped world, prescribing degrowth economics for the former and decolonial reparations for the latter. In short, Climate Justice stands for nothing short of a swift, comprehensive and deep “system change” for planet Earth.

This places us, self-identifying in affinity with the Climate Justice movement, to recognise our thoroughly urbanised, materially-privileged and socially-progressive status to be a comparable position to the (white, European, bourgeois) abolitionists of the late 18th century. We openly and unambiguously call for radical carbon emission reductions (as an insufficient yet approximate numerical indicator for the privileges of the few), which imply drastic changes in the material conditions that shape our lives in the Netherlands, as one of the most intensively modernised parts of the core countries in the globalised world-system. These lands have a disproportionate per capita share of historical and present-day consumption, emission, pollution and waste streams, notwithstanding their unequal distribution within the national borders. Therefore we are confronted with a monumental contradiction: Climate Justice entails not only giving up on but proactively abolishing the civilisational model that makes our lifestyle possible.

Taking into account the imperfect and partial understanding of geochemical systems and the precautionary principle in risk management, we consider halving emissions every decade (or 10% every year) to be an approximative indicator for the scale and ambition necessary to avert the worst consequences of crossing the tipping points of climate and biodiversity and to protect the livelihoods of billions of people. This poses great challenges for conceiving and implementing a just, rapid and effective eco-social transition within the timeframe dictated by the biophysical limits. We lack methodologies that combine and harmonise ecological imperatives, economic models, democratic processes and fundamental rights. The fragmentation and seeming contradictions between various rights-holders (workers, consumers, impacted communities) creates a deadlock in governance and maintains the status quo. Recent political crises (such as diesel taxation in France, nitrogen reductions in the Netherlands and gas shortages in Europe) lead to legitimate social grievances that remain disregarded by governments and get captured by climate-denying far-right populism. A “Just Transition” is therefore not a fanciful slogan or wishful thinking, but the only politically realistic programme that can combine appeasing social tensions and revitalising civic engagement with climate justice on a global scale.

The spatial implications of an eco-social transition are manifold, in particular in The Netherlands. Since environmental damage and depletion are unevenly distributed in society and burden the poorest and most marginalised communities the most, a Just Transition has to carry spatially differentiated outcomes. While there may be countless potential interventions to increase adaptation and resilience of a low-lying, high-risk region like the Low Countries, Climate Justice principles compel us to prioritise efforts on mitigation of harmful sectors in the Netherlands for reducing their impacts on the most vulnerable elsewhere (for instance, Ganges Delta, another low-lying region). We consider the existence of powerful, resourceful and influential industries like petrochemicals, monocultures and aviation in the Netherlands to be the primary obstacle in front of a Just Transition. We believe it is the historical and ethical duty of overdeveloped countries to decommission and dismantle these industries to repair and heal the damages they have caused and profited from. In other words, abolishing harmful infrastructures is a precondition to building resilient, sustainable ones in their place. The spatial impact of such a transition in the Netherlands will be enormous, similar in ambition to the post-war rebuilding efforts.

We acknowledge that there is currently no political majority in the overdeveloped nations to support such disruptive changes, especially in the name of protecting affected people far away. There are, however, countless examples of injustice and misery in our immediate living environments, caused by the ravages of forty years of neoliberalism. Tackling the housing crisis, energy crisis and cost of living crisis without addressing root causes and transition imperatives will only increase the vulnerabilities of an already brittle system, wasting precious resources and limited time. There are instead great synergies that can be harnessed in deploying a rugged but compassionate infrastructure that can withstand the rough ride of the 21st century. This is why the frontlines of crises are also meant to be the leaders of the transition: it is by weaving issues, struggles and solutions that power and resilience can be built and safeguarded without perpetuating or aggravating already entrenched injustices.

It is unquestionably daunting for spatial designers and planners to initiate multi-scalar and cosmo-local projects that simultaneously deploy immediate solutions and engage in “cathedral thinking” and provide intergenerational care and repair. And yet it is these disciplines that can best develop postcapitalist, regenerative and reparative pathways that are informed by science-based models and forecasts. What timescales do we invest and build for, considering unmanageable sea level rise scenarios? How to simultaneously build settlements, produce food and regenerate biodiversity in a limited space? Which movement and community demands can be translated into spatial programs? Intersecting Climate Justice and Spatial Justice means advancing research-led designs and propositions that answer these challenges by providing more opportunities than inconveniences for all those involved.

Leave a comment